I have a friend who went on a silent retreat recently: a whole weekend of no talking, no distractions and lots of meditation.

This sounds simultaneously wonderful and horrendous to me: wonderful because I can’t imagine many things as blissful right now as having no distractions, and some time for myself; horrendous because I would find switching off for that long so challenging.

I don’t know about you, but I find it quite hard to meditate. It’s incredibly difficult to stop thinking. I know the theory- recognise the thought or distraction and then let it go, but it’s quite frustrating to do!

And I will keep at it. But I actually find exercise to be a form of meditation, and I find it easier to lose myself and focus on the moment when training than when trying to meditate.

When running I focus on the way my foot strikes the ground, the way my body moves onto it and how my foot then propels me forward again. I feel how smooth the movement is; am I wasting energy bouncing up and down or can I maintain an efficient forward propulsion? And my breath, the rhythm of it.

I used to throw on my headphones and plod away, enjoying the rush of exercise, the challenge of beating my times, but not always the process itself. Since switching to a forefoot strike and becoming aware of technique, running has become much more meditative for me.

I had a similar experience with swimming, where slowing down and trying to achieve a more efficient,smoother stroke has kept my mind on what I’m doing in the water, rather than just singing in my head while I notch up the lengths.

But what are the benefits of mindful exercise?

Sure, I feel calmer, more relaxed and more clear headed after training like this. And I feel like my movement is more efficient. But what’s the science behind it?

Increased skill.

Have you seen the video where you have to count the number of ball passes between the players? If you haven’t here it is:

It beautifully demonstrates how we can only really be aware of some of the sensory information our body is receiving. And when we focus on how something feels, that we weren’t fully aware of before, we excite neural activity. This is why, according to Todd Hargrove in A Guide To Better Movement, “focussed attention is one of the key requirements for practise that maximises neuroplasticity and associated motor learning.”

So to gain the most from practising any skill, you need to be fully focussed on it. This kind of tunnel vision is something top athletes tend to excel at.

Decreased risk of injury.

When we focus on particular sensations in our body we can also improve the sensory information our bodies send our brain. This is kind of important!

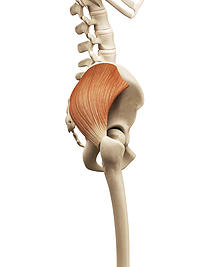

Our brain has a sort of ‘map’ of our body, and our nervous system sends it information. Poor proprioreception means the information being sent to the brain is poor, often as a result of poorly facilitated muscles. Think of the difference between someone who closes their eyes and wobbles all over the place and a gymnast who does the same and remains still.

If the brain isn’t confident that a joint is stable, it can restrict range of motion in an attempt to protect it. And if the ‘body map’ in the brain is poor then movement control will suffer. Which means an increased risk of injury!

So to improve your proprioreception, regular mindful movements are best, and ideally they should be complex and novel, as these result in a stronger neural response. Do this by consciously trying to squeeze the muscles you know should be working. Over time it will become more subconscious.

A stronger muscular contraction.

The other advantage to focusing on the muscle being worked is it actually works a lot harder!

This article examines this by conducting a study into the effect of the mind-muscle connection on resistance training. If you’re interested then follow the link for more information, but it shows just how large an effect mindful focus can have.

It’s something I’ve been taught is especially important when coaching kegels, as many women can actually contract the wrong muscles, say the glutes, and not train the pelvic floor effectively. Many Women’s Health Physiotherapists will show their patient a model of the pelvis to aid this with visualisation, and I like to encourage clients to imagine drawing the pubis and coccyx (where the pelvic floor attaches) together.

In this blog physiotherapist and pelvic floor expert Sue Croft describes how effective using the model is, as she can “confirm that I can often feel a stronger contraction on palpation, when the patient views the model compared to not looking at it.”

So there you have it, whether meditation isn’t your thing, or if you’re just not that great at it yet like me, you can still reap some of the benefits by applying mindfulness to you workout!